The Thistlegorm - Egypt

The legendary SS Thistlegorm is the best known shipwreck in the Red Sea.

The 125m long British army freighter was used in World War II and on its way to the Suez Canal when it was sunk by a German airstrike in the middle of the night October 5th-6th 1941.

This incredible underwater museum is so iconic and unforgettable, it should feature high on the bucket list of every scuba diver.

It now rests on the west coast of the Sinai Peninsula around 40 km from Sharm El Sheikh.

This article was is part of the “Get wrecked” series written by Edwin and originally published in the diving magazine of Lucky Divers Rotterdan (The Netherlands)

You can view the article by clicking on the image

NOTE: At this time the PDF of the published article is only available in Dutch.

Sorry for the inconvenience.

Click to view the original article as PDF (Dutch)

The Thistlegorm (Red Sea - Egypt)

This time we discuss the “Salem Express”, (Fred Scamaroni ) christened during its launch.

Bought by the Egyptian government, the ship ensured the connection between Port Jeddah (Saudi Arabia) and Port Safaga (Egypt).

The ship met a very tragic end that will remain etched in the memories of hundreds of Egyptian families for a long time.

We dived this wreck togheter only once in 2008 during our divemaster course.

NOTE: We make use of “Sketchfab” click HERE to view the navigation controls

Click on the 3D model below to move it around

Specific Photogrammetry areas of the Thistlegorm

All credits of the models below go to Simon Brown of DEEP3D

Click on the ‘play’ button to activate the animation.

When active press’f’ key for fullscreen. (Press ‘Esc’ key to return)

Thistlegorm – Port side Locomotive

Thistlegorm – Starboard Locomotive

Thistlegorm – Captain’s Room

Thistlegorm – Bridge Room

Thistlegorm – Deck one

Thistlegorm – Deck two

Thistlegorm – Holds 1 & 2 of deck two

Thistlegorm – The rope room

The story & the dive

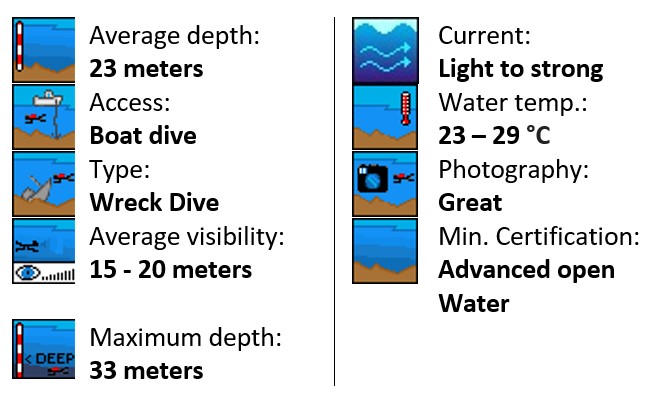

The data

- Type: Cargo Ship (Armed)

- Launched: 9 April 1940, by Mrs K.W. Black

- Tonnage: 4898 tons

- Length: 126.5 meters / Width: 17.7 meters

- Draught: 7.45 metres

- Power: 3 cylinder steam / 1850 HP

- Speed: 12.5 knots

- Date of Sinking: October 6, 1940

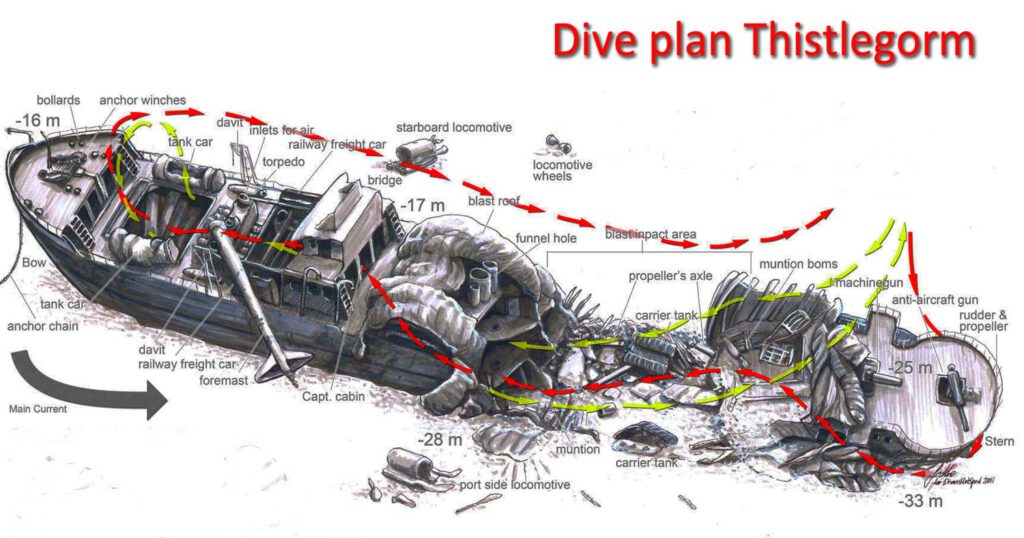

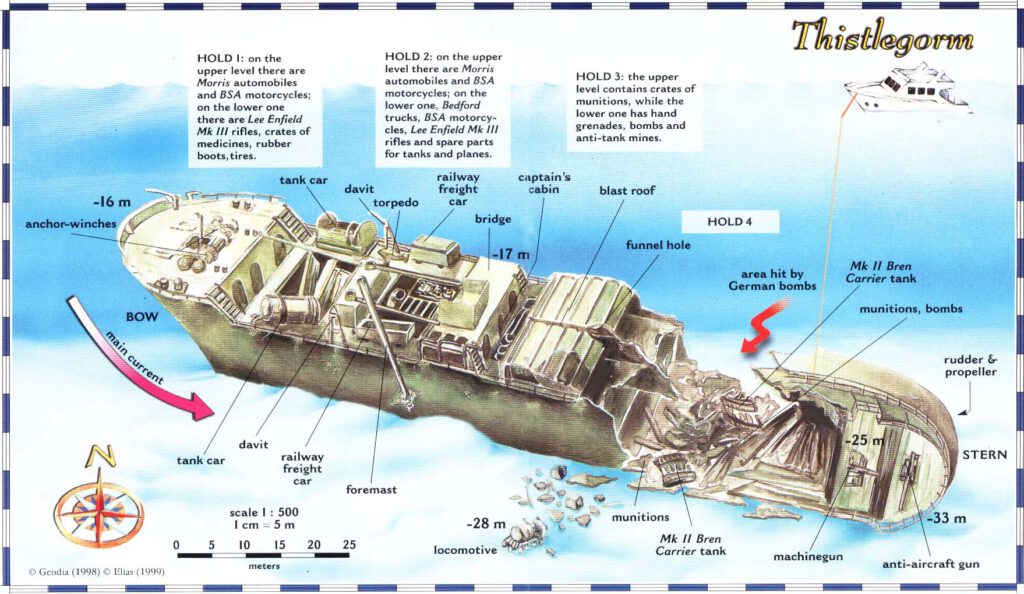

- Minimum depth of wreck: 16 meters (at the bridge)

- Maximum depth to seabed: approx. 33 metres

- Current location: 27 48.849N, 33 55.222E

- (North-East of Shag Rock, Sha’ab Ali, Egypt)

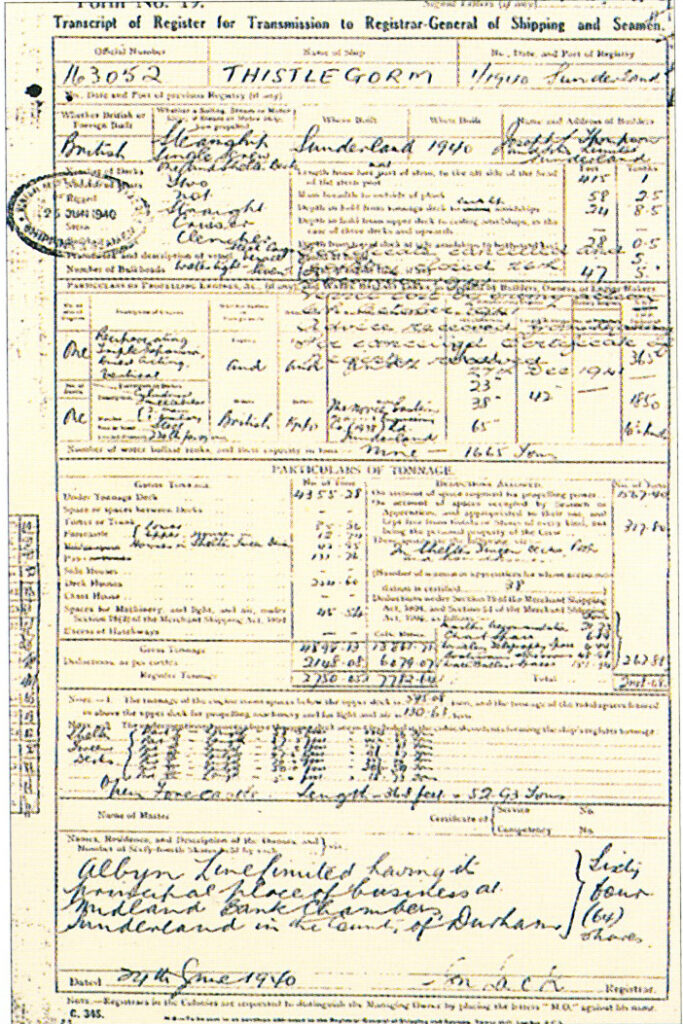

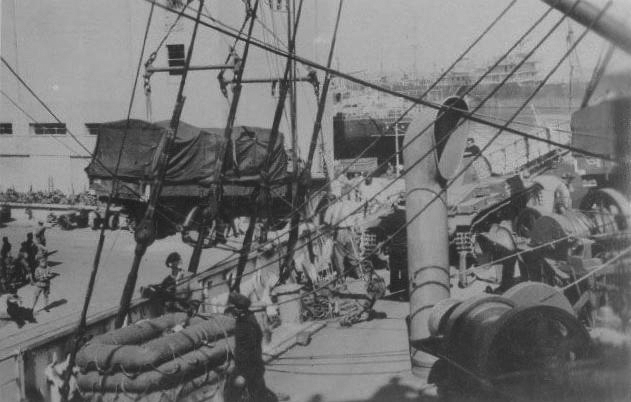

The Thistlegorm during it’s launch in 1940

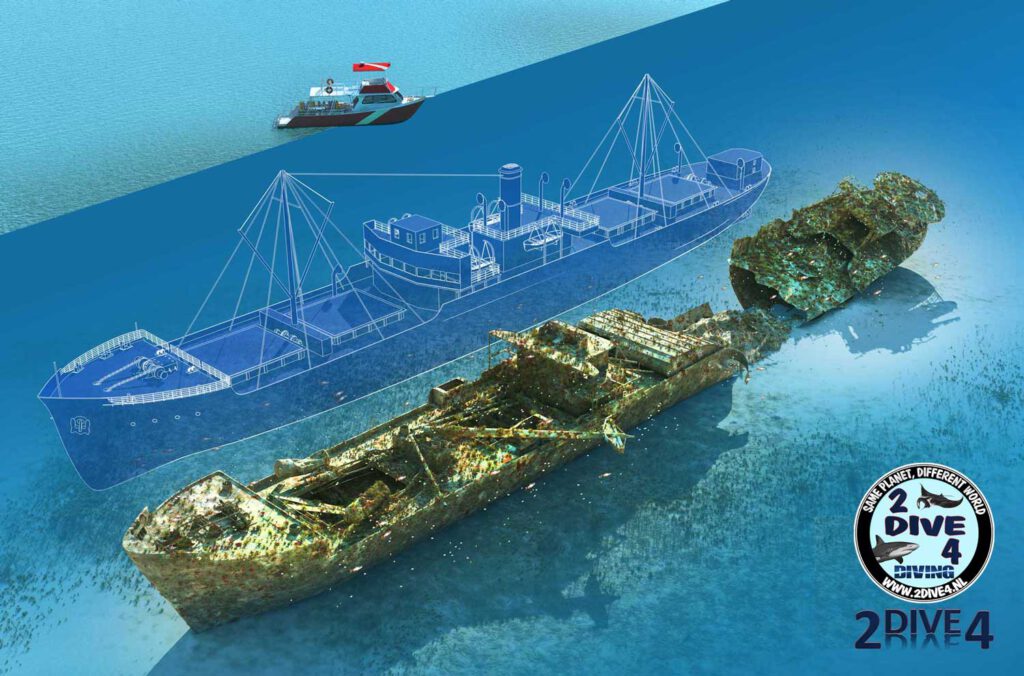

The ship

This time we discuss one of the most famous and most dived wrecks of the Red Sea; the “Thistlegorm”.

In 1940, England lost more ships than she could build during the beginning of the war. The German submarines caused great damage to the English fleet. Due to the high demand for shipbuilders in Sunderland near Newcastle, Scotland, the shipyard of Joseph L. Thompson & Sons Ltd was approached to build ships for the Scottish Albyn Line. (The shipyard no longer exists since 1966)

One of the ships built by this yard was the Thistlegorm.

The Thistlegorm was just one of the “Thistle” ships that Albyn Line owned and was used for the navy. Despite the status of “Armed Freighter”, there was not much armament available on the Thistlegorm.

On the armored deck was only an old 4.7″ (120mm) anti-aircraft gun and a heavy caliber machine gun, both of which had already served in WW1.

The first voyage of the Thistlegorm went to the USA to pick up steel rails and airplanes.

Her 2nd trip was to Argentina on this trip a shooting exercise was held on the ocean with the 4.7″ anti-aircraft guns, unfortunately it remained at 2 shots….

After the first shot was successfully fired, the 2nd grenade got stuck, with the help of a rope the trigger was very carefully pulled again to fire the grenade. The result was that with a huge explosion the grenade eventually left the barrel and then fell into the sea 50 meters away from the ship. All shooting exercises were canceled. The third trip was to the Dutch East Indies, to get grain and rum.

Unloading in Tripolis

The Thistlegorm was just one of the “Thistle” ships that Albyn Line owned and was used for the navy. Despite the status of “Armed Freighter”, there was not much armament available on the Thistlegorm.

On the armored deck was only an old 4.7″ (120mm) anti-aircraft gun and a heavy caliber machine gun, both of which had already served in WW1.

The first voyage of the Thistlegorm went to the USA to pick up steel rails and airplanes.

Her 2nd trip was to Argentina on this trip a shooting exercise was held on the ocean with the 4.7″ anti-aircraft guns, unfortunately it remained at 2 shots….

After the first shot was successfully fired, the 2nd grenade got stuck, with the help of a rope the trigger was very carefully pulled again to fire the grenade. The result was that with a huge explosion the grenade eventually left the barrel and then fell into the sea 50 meters away from the ship. All shooting exercises were canceled. The third trip was to the Dutch East Indies, to get grain and rum.

Since the Albyn Line was a commercial company, the engines were loaded on the back of the trucks to save loading space. In addition, 2 locomotives were put on board, both with a trailer and a water supply wagon for the Egyptian railways. The 6 trainsets were taken as “Deck cargo”. Because the ship was an “armed freighter”, Captain William Ellis had a team of 9 “Royal Navy” marines on board to operate the weapons.

Captain William Ellis

The story

On 2 June 1941, Captain William Ellis ordered the mooring lines to be cast off and set sail for open water.

Via the west coast of the British mainland, it sailed to a secret meeting place on the south coast of England where it joined a large convoy and was given a prominent place within the convoy because of its armament.

From here on the relatively safe route via South Africa was chosen, after refueling in Cape Town the 4190 ton cruiser HMS Carlisle was added to the convoy. Then course was set via the east coast of Africa to the Red Sea. When they reached the Gulf of Suez it was now the 3rd week of September and the Thistlegorm was immediately referred to “Safe Anchorage F” (an anchorage that was supposed to be safe) Captain Ellis was relieved that the voyage had gone so smoothly and anchored the ship in the 250 meter deep water.

The engines were switched off while waiting for permission to sail on to Alexandria. Permission to continue sailing was influenced by various factors, including enemy aircraft activity over the channel, priority of the cargo and how long a ship had been waiting. Further in the Gulf of Suez, 2 ships had run into each other and blocked the entrance to the canal. As a result, the Thistlegorm with its important cargo had to wait no less than 2 weeks to continue sailing.

These “Safe Anchorages” places were indeed safe from enemy fire until now. This changed when German intelligence had information stating that a large ship with troops (probably the Queen Mary) with 1200 men to man South Africa was about to pass through the Suez Canal.

With the relatively new technique of “night flying”, Henkel He 111s of the II/Kg26 (No 2 Squadron 26th Camp Geswader) were sent into the air from their base on Crete (Greece) with the order to locate and destroy this ship.

The Heinkel He 111 bomber

A Henkel 111 armed with a 1,000-kilo bomb

A 1000 kilo cylinder bomb Type SC-1000 L at a Henkel

The sinking of the Thistlegorm taken from the Henkel He 111

Late in the evening on October 5, 1941, 2 “win-engine Heinkels” flew over the northern Egyptian coast in a southeasterly direction in search of the ship. During this clear night, the Henkels searched in vain for the large ship, as their fuel level had dropped considerably, they decided to return to their base ’empty-handed’. German ‘Gründlichkeit’ can also fail sometimes…..

The planes are about to fly back to base, but just before they started the return course, one of the crew members saw a ship anchored, the Thistlegorm…. And they decide to attack immediately. The Henkel made a wide turn and then flew low over the Red Sea and approached the bow of the Thistlegorm, dropping 2 bombs just over the bridge of the ship. The bombs penetrated cargo hold no. 5 and caused a huge explosion because a large part of the ammunition exploded at the same time. The explosion sent the 2 locomotives flying through the air, and the ship was then ripped up like a can.

The ship immediately began to sink and the crew quickly left the ship.

Angus McLeay

Due to the rapid sinking, the crew did not have time to use the lifeboats and immediately jumped into the sea.

An injured crew member was still trapped on the hit deck and needed urgent help.

Crew member Angus McLeay quickly wrapped some cloths around his bare feet and then ran across the red-hot and broken-glass covered steel deck to rescue the man.

For this action, McLeay would later be awarded the “George Medal” and the “Lloyd’s War Medal for Bravery at Sea”

Due to the rapid air attack, the Thistlegorm had no chance to defend itself and sank immediately. It was now 01:30 on October 6, 1941.

Captain Ellis and the other survivors were rescued by HMS Carlisle and transferred to Suez where he reported that 4 of his crew and 5 of the Royal Navy marines had not survived the attack.

HMS Carlisle

Part of the Thistlegorm crew

Captain Ellis was later awarded the “War Services” by King George VI. But the crew of the planes was also not very lucky. A guardship of the convoy took them at such gunpoint that one of them had to make an emergency landing on the water.

The crew was able to reach the saving bank of the Sinai in a rubber boat, but was captured by British soldiers a little later.

In October 1943, HMS Carlisle was so badly damaged in the Scarpanto Strait by Junkers 87 D-Stukas of the II Gruppe/StG 3 from Eleusis near Athens

She was taken in tow to Alexandria by Rockwood. She was considered to be beyond economical repair as a warship, and instead was converted to serve as a base ship in the harbour of Alexandria in March 1944. She was last listed as a hulk in 1948 after the war had ended, and was broken up in 1949.

Bombing of the HMS Carlisle

Crew interviews

Excerpts from live interviews with actual survivors of SS Thistlegorm under attack in 1941:

Glyn Owen

“I heard a plane making what appeared to be a second run or at least sounded like a diving run and my training I suppose came out and I just flung myself out of my hammock on the deck beneath and crouched behind a winch and then there was just two explosions and a mass of flame and my hammock above my head caught fire.”

Ray Gibson

“…I was on watch behind the bridge, and next thing there was a big bang and I realised we had been either bombed or torpedoed, one of the two, but we’d been hit by enemy action…..”

Angus McLeay

“I made for the side to jump overboard and the rail was almost red-hot under my hand. I don’t know why, but, just as I was going to jump, I looked back and saw the gunner crawling along the deck on the other side. The deck was covered with broken glass and I had to take the bits out of my feet before I could carry the gunner through the flames, which came up to my chest in places.”

John Whitham

“I was on watch at twelve o’clock and about one o’clock we heard the sound of aircraft. We looked across to the Carlisle and there was nothing indicating from her and the sound of the aircraft got nearer and the first thing that we realised was that he was planting a few bombs on us, which, unfortunately, dropped in number four hold, possible number five, but number four I do know, because there was some flames shooting out from there and we……we’d quite a good fire going for a while.”

Denis Gray

“…it seemed like two or three minutes I would think, that this huge explosion took place and of course we were looking in the direction of the Thistlegorm at the time and shortly after the explosion there was a huge sheet of flame which lit up both sides of the Red Sea at that point, we could see it light up the Mount Sinai on one side and Egypt on the other side and all the ships and everything around and then all of a sudden there seemed to be a second explosion and still looking in that d irection we were amazed to see what turned out to be a railway engine and it was red hot with sparks flying from it and it was coming in our direction.”

The discovery

Jacues Yves Cousteau

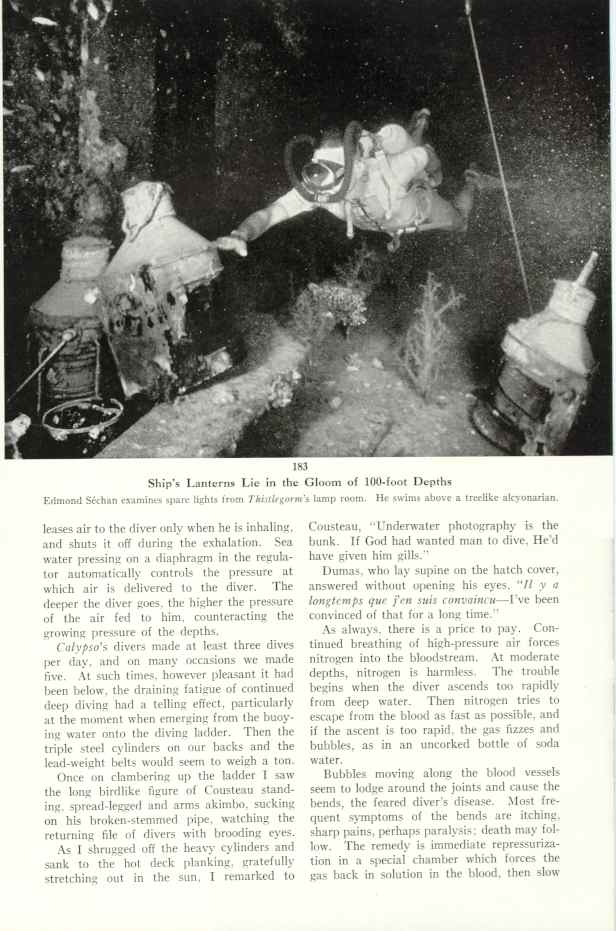

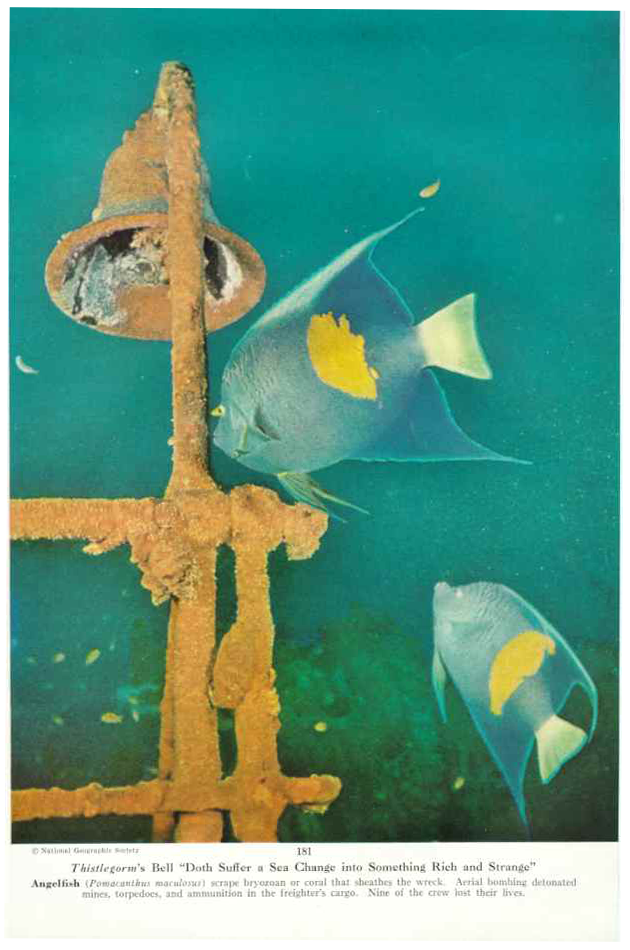

The war rages on and the ship is forgotten until it is found in 1956 by none other than Jacques-Yves Cousteau on one of his first expeditions with his legendary ship the Calypso.

Cousteau finds the ship’s bell with the inscription: S.S. THISTLEGORM, GLASGOW.

They take the captain’s compass and safe, only to find the captain’s wallet with 2 Canadian dollars in it. The February 1956 edition of “National Geographic” clearly shows the ship’s bell in its original location and Cousteau’s divers in the “Lantern Room”.

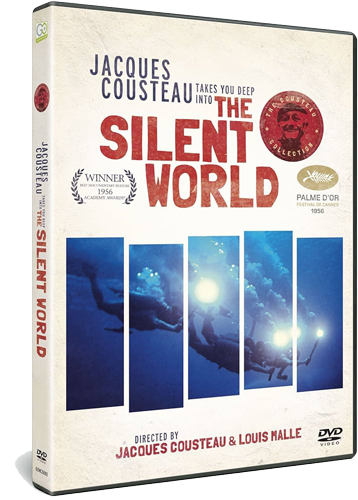

His discovery has been captured on film and can be seen on the DVD “The Silent World”

The classic ‘Silent World’ was made by the legendary documentary filmmaker Jacques Cousteau, in collaboration with the equally famous filmmaker Louis Malle.

The film won the Golden Palm in Cannes in 1956 – and even an Oscar in 1957.

In the February 1956 issue, ow photographer Louis Morden describes his impressions of the ‘Thistlegorm’ in National Geographic:

NGC issue january 1956

(Click to read)

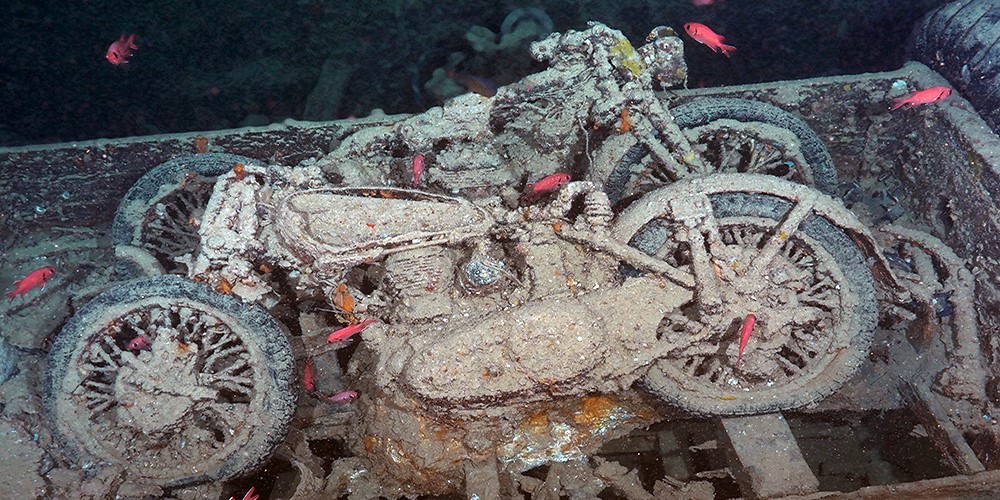

“Between the dented tank wagons, the dark hole of the main cargo hold yawns.

I lower myself very slowly and, when my eyes are used to the semi-darkness, I see whole rows of trucks.

There are countless motorcycles on every truck.

All kinds of corals, fungi and oysters have settled on the metal of the motorcycles, only the black rubber tires are almost flawless. Between the trucks are the metal supports of aircraft carriers”.

When we swam down past the wheelhouse again, Dumas pointed to the sign with the name of the shipyard, which was attached to a bulkhead.

‘When we swam down past the wheelhouse again, Dumas pointed to the sign. He swept away the silt and some small corals and we read:

Joseph L Thompson & Sons, Limited, North Sands Shipbuilding Yard, No. 599, Manor Quay Works, 1940, Sunderland. Now we knew we were dealing with an English ship, but it took days before we found out the name, because we didn’t want to clean the ship’s bell until the film recordings on the foredeck were finished. Eventually we were given permission to clean the bell, revealing the name of the ship – ‘SS Thistlegorm’.”

Below a part of the movie “The silent world”by Jacques Yves Cousteau where the Thistlegorm is discovered.

The "Re-discovery"

For almost 20 years, Cousteau’s secret about the Thistlegorm has been preserved. Until in 1974, the Israeli diver Shimshon Macchiah was brought to the ship by a fisherman from El-Tur.

Macchiah did not reveal his secret until he took a group of Swiss divers to the wreck in 1985, and even in the following years the existence of the ship was only known to a small group of local divers, according to the book “The Great Shipwrecks of the Red Sea” by Alberto Siliotti

Roger Winter

The real “rediscovery” of the ship was only done in May 1992 by Roger Winter, a skipper in Hurghada, the news was then brought out only in May 1993 when journalist John Bantin published an article in the English magazine “Diver” All experts agreed that in the Strait of Gubal in the Red Sea there could not be a single undiscovered wreck. Not after all the extensive research that was done in this water. Although Roger Winter was an experienced and successful wreck hunter, no one believed that he would discover a wreck in a place where diving had been going on for years; after all, everyone who dived there knew every reef and crevice. This time, however, it was different. This wreck is said to be a ship that had transported war goods. And it wasn’t just a rumor, but it was on paper, including the approximate location of the wreckage.

It was decided to search for the wreck. The ‘Lady Somaya 111’ left the port of Hurghada and sailed north, the target was the Strait of Gubal.

After reaching the intended position, the search began. The sea chart only showed a flat sandy desert, which was confirmed by the echo sounder. The second day, a signal suddenly appeared on the echo sounder at a depth of only 19 meters.

A marker buoy was thrown overboard. Suddenly a clear signal appeared. Everyone agreed that the wreck had finally been found.

While the divers squeezed into their suits, the first man jumped overboard with only his basic equipment on.

He was nervous and excited and tried to snorkel to the wreck, but it was too deep.

Roger Winter inside the cargo hole

The first divers dived to the wreck and attached a rope to it. Then the investigation began.

They find mountains of rubber boots and car tires, which are not yet overgrown and look like they came straight from the factory, corals do not seem to find a foothold on them.

The sought-after wreck had been found, but which wreck was it? Neither the name nor the cause of the demise was known. But it was precisely this data that mattered. Figuring this out became quite a puzzle. Under what circumstances had the ship sank? What was its mission? Where did it come from? Questions to which they did not know the answer.

To begin with, the name of the ship had to be found first. The fact was that it had to be an English ship, because they had found the name of the shipbuilder on the wreck itself: ‘Joseph L. Thompson & Sons Ltd., Sunderland, 1940’. This shipyard no longer existed since 1988 and the requests to various archives in England were also unsuccessful.

An advertisement in a British naval magazine in the form of an appeal to survivors of a shipping disaster in the Red Sea during World War II to come forward put them on the right track.

Two survivors came forward and one of them still remembered the name of a third. And so it went on, until they finally found out the name of the ship: ‘SS Thistlegorm’. The participants of the expedition were in for an unpleasant surprise when they learned that Jacques-Yves Cousteau had already dived on the wreck in the mid-fifties.

They had to accept that they were not the original discoverers of the ship that sank in 1941.

On board at the time was the underwater photographer Louis Morden of the National Geographic Magazine who documented the trip. The story of Roger Winter is also recorded in the ZDF film “Tauchfahrt in die Vergangenheit – Das Wrack der SS Thistlegorm”

The dive site

Most wrecks in the Red Sea have sunk because they walked on the reef. They are therefore often in the immediate vicinity of a reef. The Thistlegorm, however, stands in the middle of the sandy bottom at a depth of more than 30 meters.

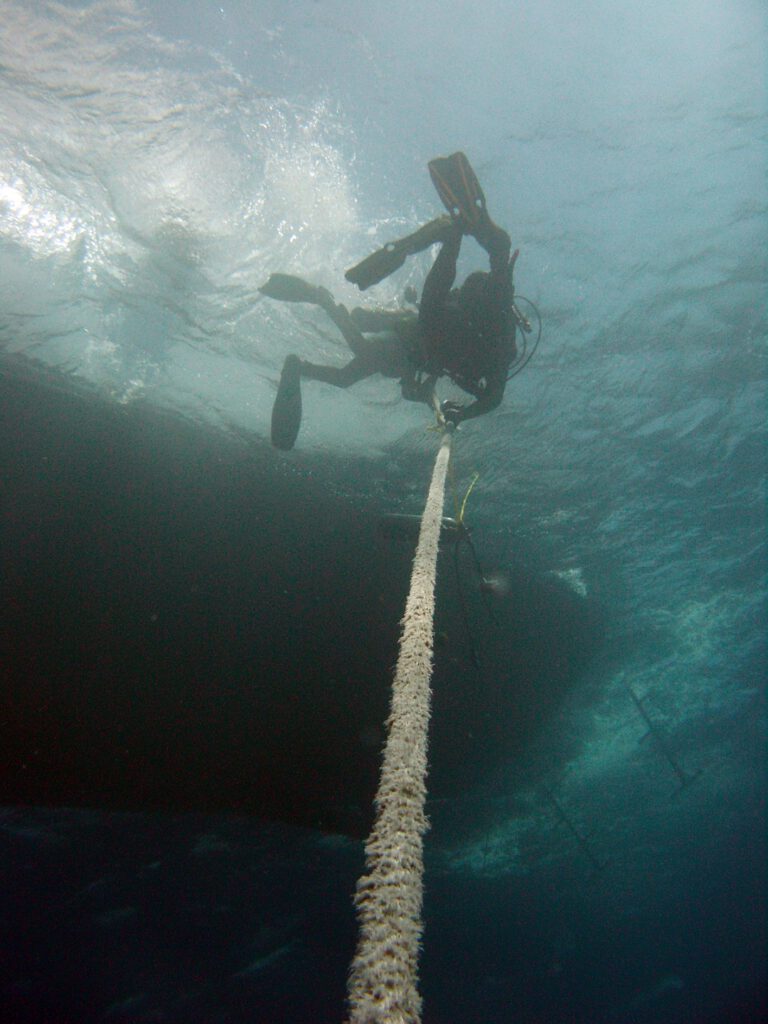

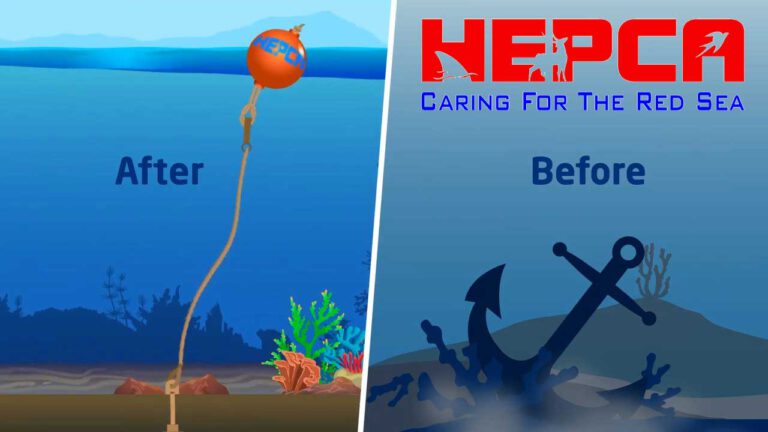

For several years now, HEPCA has placed so-called ‘mooring buoys’ around the wreck to which the submarines can be moored. Above the wreck it is always busy. Be careful because the currents can be quite strong around the ship!

Underwater life

There is a lot of marine life present on and around the wreck. Perch, napoleons, schools of barracudas and snappers, … the Thistlegorm forms, as it were, an artificially created reef. Various fish species have made the Thistlegorm their home, turtles are also regularly spotted in the holds. Around this historic wreck it is teeming with fish, such as barracudas and tuna, which in turn chase large swarms of glassfish. Everywhere on the wreck you will find beautifully colored soft coral.

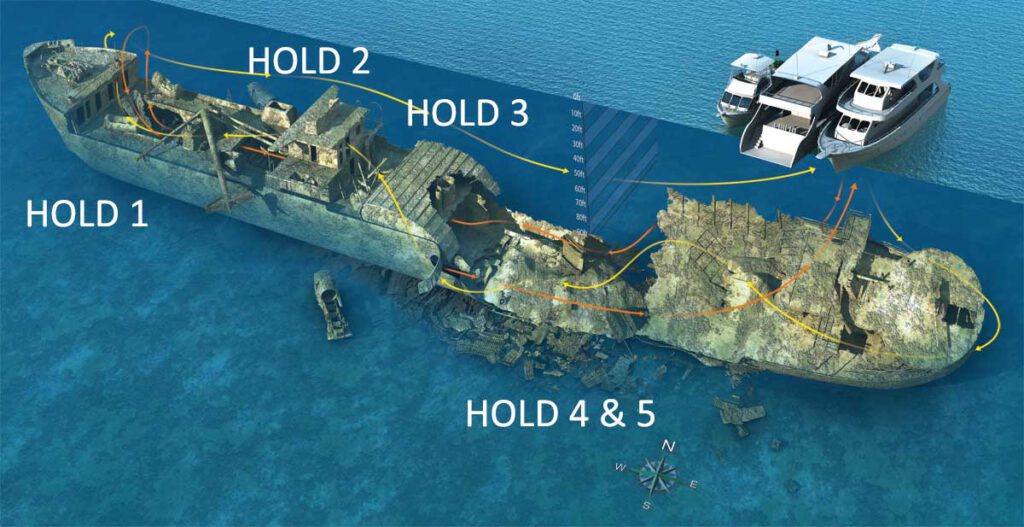

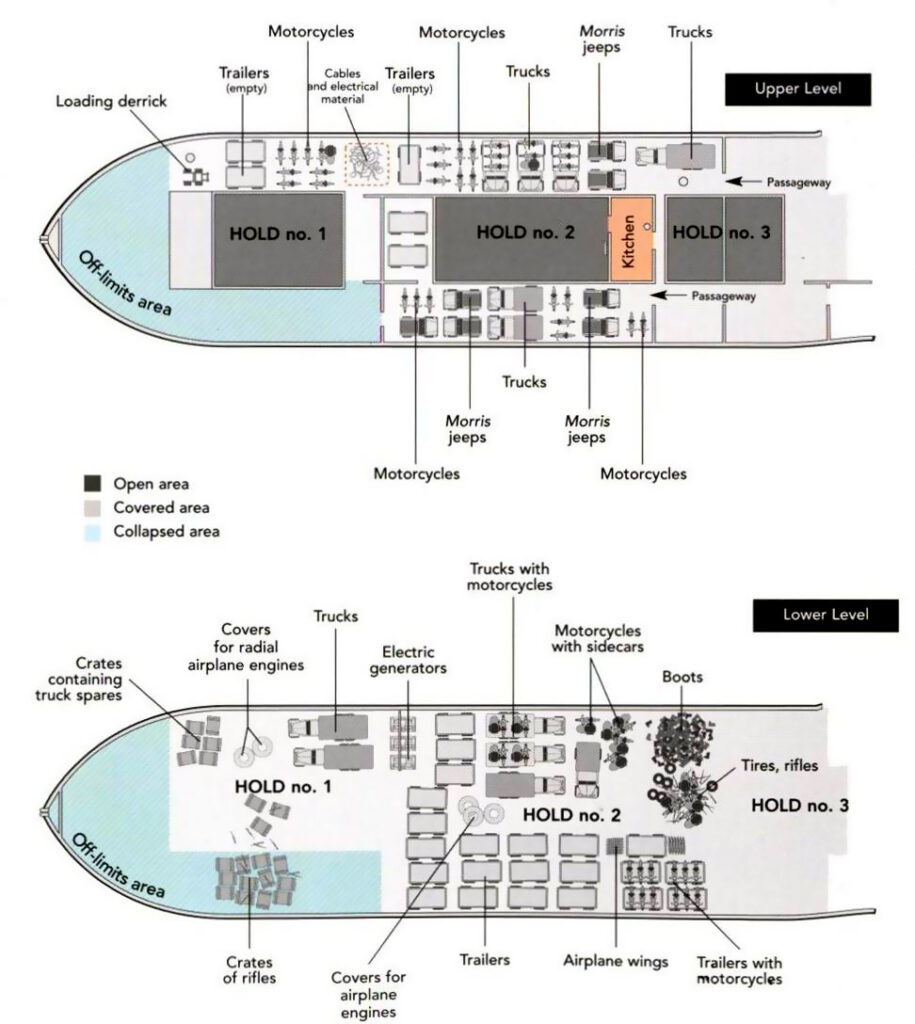

Sights

The war material that the Thistlegorm was carrying is on and around the ship and in three holds.

It includes uniforms for the troops some Morris and Bedford brand cars, railway wagons, locomotives, MK-III rifles, ammunition, landmines and hand grenades, 2 MK II Bren Carrier tanks to be found. (The Bedford trucks are even still loaded with the BSA motorcycles.)

Inside the wreck there are 3 holds to visit (holds 4 and 5 have been completely destroyed by the explosion)

The images below show some layouts of the wreck:

The dive

The Thistlegorm is undoubtedly one of the most famous wrecks of the Red Sea. It has a huge appeal to divers. This is mainly due to its special history. To get a good impression of this huge wreck you will have to make several dives. The ‘Thistlegorm’ lies at a maximum depth of 33 meters, the largely intact bow stands almost upright in the sandy bottom.

The middle part was badly damaged by the explosion. In general, it is wise to dive with nitrox on this wreck (provided you are certified for this, of course). Even with nitrox you will see that your bottom time will feel like a lot shorter…….. There is so much to see that it is almost an ‘obligation’ to make more than 1 dive.

Around the wreck

It is wise to start your dive at the stern as this is the deepest part. Descend here and take a look at the propeller. Swim around the back and now check out the 120mm anti-aircraft gun and the 39mm gun that are on the deck.

On this side of the ship there is also a locomotive at a depth of 33 meters, which came off the deck during the sinking. Definitely worth a look for enthusiasts , but think of the depth!

Continue your way over cargo hold 4 and 5 which are completely destroyed, here you will find a lot of ammunition. Take off slightly to go towards the bridge, just before the bridge is the captain’s cabin, you can even visit the captain’s bathroom, where numerous tube worms grow in the bathtub .

The bridge is in good condition, and if you want to enter easily. Continue your way via the port side of the ship towards the tank wagon that is on the deck. From here you can continue to the bow where you can find the windlass.

Go back to the stern via the starboard side. First you come across another tank car with a large torpedo directly behind it. Then there is a train carriage after which you will pass the bridge again. Swim over cargo hold 4 and 5 again towards the back of the ship where you can start your ascent.

In the wreck

I (Edwin) have been able to make several dives on the Thistlegorm, dives around the ship as described above and also dives in the ship. I often think back to the latter…

But I will never forge my first dive in the Thistlegorm….being an advanced open water diver with about 20 logged dives penetrating the Thistlegorm is NOT a wise idea…..

Well, that’s to say the least; not smart…

But with a body full of adrenaline and a big plate in front of my head, I jumped in to meet the Thistlegorm.

Accompanied by a very small diveguide called “Esat” and two fellow buddies we started our adventure.

Esat had asked us in advance if we wanted to see the Thistlegorm from the inside, well we liked that.

Also his question; “I mean, do you REALLY want to see the Thistlegorm” we answer in the affirmative…. To which Esat said: “OK, then we go to the wooden room”.

So when we arrived on the reck we entered via cargo hold 4, and then the first to visit cargo hold 3. This is full of ammunition, from (hand) grenades to anti-tank mines, it is there….further back you come across a few trucks and motorcycles. We swim on to hold 2, here are again some trucks and rows of motorcycles.

Aircraft parts such as wings are also neatly stacked here. I am slowly starting to feel a bit uncomfortable, we are already quite far in the wreck, and we also meet fewer and fewer divers……

Anyway, after a few OK signs towards my buddies further into the wreck…. Hold 1, here too it is full of guns, clothing, boots, motorcycles and trucks.

It is now pitch dark in this part of the ship and we rely on our lights. Has anyone seen Esat……? Ehhhh, you know our diveguide….. With some fear in my legs I look at my buddies, they were no better off than I am I can tell you…..

Sea fan in the ‘wooden room’

Finaly we saw Esat, he beckons us with his lamp. Esat sits on the other side of a metal partition of the ship, and motions us to come to his side….

I look at the hole in the wall, then look at my own size…. Then look at the hole again….and came to the conclusion that this was not going to fit…….

As mentioned, Esat was probably the smallest diveguide in Egypt, so no problem for him, but for 3 Dutch guys this was a bit less easy…. Eset motioned us to take off the Jackets to squeeze through the small passage, and so we did, jacket first through the hole and then after it himself …

Pfff, is that all……

We are now in a small enclosure with some wooden walls, Ahhhh now we understand “the wooden room”! We then squeeze back through the opening, not entirely harmless because there are also sharp pieces of metal sticking out. When all 4 of us have ended up in the previous room, our computers start beeping 1 by 1….. DECO…..

Well that’s nice… when you’re in the middle of a wreck… at 30 meters of depth..

Fortunately Esat knows another way out through the bow of the ship, after some more struggling through hold 1 we see light at the end of the hold !! Here we can accent and to our great surprise we come out of the ship next to the windlass….. 15 minutes of deco was the result.

After 3 safety stops, our computers finally gave the green light to leave the water. With 11 bar left in my tank I go on board, Thank God for 15 liter tanks !!

So this is a typical case of how it SHOULD NOT be done! I have told this before, but unfortunately these kinds of ‘blunders’ happen all too often, and I was indeed guilty of them.

The inexperience, not wanting to be left behind by ‘experienced’ buddies and underestimating the danger are often the cause of this.

Fortunately, this time it ended well, but unfortunately there are many examples that it did not end so well.

Preserving the Thistlegorm

Mooring buoys around the Thistlegorm

In 2008 I (Edwin) was privileged to join the mooring bouy team of the Thistlegorm for 2 days.

A collective commitment of diving centers and volunteers offered help and provided facilities to make the work happen.

This team took care of adding 32 mooring bouys around the Thistlegorm in order to avoid anchoring on the wreck.

The HEPCA mooring team successfully completed work on the 6th April 2008!

All the lines are now fitted with steel eyelets to make tying on easier, and each line has a buoy to aid easier identification.

In addition, boats are no longer permitted to use the mooring system unless they throw an anchor from the stern.

This extra stability should help to ensure that the lines do not become shredded by rubbing against the structure of the wreck in wind and strong currents.

Below a movie of HEPCA explaining the need of mooring bouys

Dive or not?

As many of the Red Sea wrecks the Thistlegorm also encountered casualties.

Nine men (5 gunners and 4 merchant seamen) died in the attack but the rest of the 41 crew managed to escape the burning ship before the munition on board resulted in a massive explosion which broke the wreck in half and took it quickly to the bottom.

So if you’ll dive the Thistlegorm treat the site with the utmost respect for the men who lost their lives.

Always remember the sanctity of the site: it is a war grave

In memoriam

Dedicated to the men who lost their lives on the 6th of October 1941

Arthur Cain – Aged 26

Archibald ‘Archie’ Giffin – Aged 18

Alfred Oswald Kean – Aged 68

Donald Masterson – Aged 32

Joseph Munro Rolfe – Aged 17

Kahil Sakando – Aged 49

Christopher Todds – Aged 25

Alexander Neil Brian Watt – Aged 21

Thomas Woolaghan – Aged 24

Conclusion

Almost all current divers only know the Second World War from history books, from movies or documentaries.

A dive on this ship is truly a tangible piece of history, as if time has stood still.

Boots still seem perfectly usable, trucks neatly arranged as they were placed there, crates with weapons and ammunition ready for use….

More than 85 years later and still so recognizable. It takes some time to process all these impressions.

A second dive gives you the chance to get a better overview. But don’t make a 2nd dive like I once did…….

From Sharm el Sheikh, travel time is around 3 1/2 to 4 hours.

From Hurghada, this dive can only be made in combination with a mini safari (with a minimum of 1 night on board).

It is not excluded that you will experience a strong current during your dive and less good visibility is also possible here.

But not to mention this piece of British history is a must for every diver!

Dive information